By 1910, the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha had

reigned in the United Kingdom and the British Empire for nine years. That

year,

the first monarch of that house, Edward VII, died and was succeeded by his

eldest surviving son, George V, who had served in the Royal Navy and considered

himself to be patriotically British. Yet the royal house to which he belonged

was anything but British. It was the ancestral house of his grandfather Prince

Albert, based on the German ducal lands his family held. Even so, the fact that the

royal family was of immediate German origin was not a secret, and it did little

to diminish the overall affection that the public had for them. World War I however,

would change that.

|

|

King Edward VII

was the latest of a line of monarchs beginning with

George I in 1714 who were of German origin or descent. |

As the “war to end all wars” dragged on, Germans and

Britons of German descent became increasingly suspect in the eyes of the

British public, who were being fed stories about German war atrocities and cartoon

images of blood-thirsty German soldiers. The anti-German mood became so toxic,

that it manifested itself in riots and vandalism at homes and businesses owned by

people with Germanic names. This led to the forced resignation of Prince Louis of Battenberg – a German prince who was a decorated British naval officer of 40 years and a cousin of the royal family – from his office of First Sea Lord (which is the professional head of the British Naval Service). Eventually, the British Royal Family

itself was suspected of having too close of a connection with the enemy Hun, and not being full-heartedly

supportive of the British war effort against Germany. In fact, only the

opposite was true, but it certainly did not help being a first cousin of the

German kaiser, Wilhem II, as George V was (because both men were grandsons of

Queen Victoria). It also did the royal family no favors that it had a German

royal house name – Saxe-Coburg-Gotha – and held German titles. The writer H.G.

Wells criticized George for having an “alien and uninspiring court,” to which the king

responded, “I may be uninspiring, but I’ll be damned if I’m an alien!” But the

final straw came when Gotha G.IV planes were dropping bombs on London.

|

| King George V (center), with his two eldest sons: Prince Edward (the future Edward VIII) on the left and Prince Albert (the future George VI) to the right. |

It soon became apparent that there needed to be a

change in name for the royal family. George did not know what his actual

surname might be, so the College of Heralds was consulted, and they reported

that his name was either Guelph (the

ancestral house of the Hanoverians) or more likely Wettin (the ancestral house of the Saxe-Coburg’s). Either way,

these names did not sound British, so a search began for new name. Proposed

names included those of former royal dynasties: Plantagenet, Lancaster, and

York. Tudor-Stewart was also suggested as a way to pay homage to the House of

Tudor, which ended the fratricidal Wars of the Roses in England, as

well as the

House of Stewart/Stuart, the Scottish royal house that brought the British Isles

together under one monarch. These names were written off as either too

English-oriented (in a kingdom which included the Scots, Irish, and Welsh) or

backward-looking for a royal family attempting to re-christen itself as being

a model, modern, and thoroughly British family. Eventually, George’s private secretary, Lord Stamfordham,

suggested Windsor, after the king’s

favorite residence of Windsor Castle, which has been a seat of the monarchy

since the days of William the Conqueror, and used by Scottish and British monarchs since

James VI & I ushered in the Union of the Crowns. There was also some

historical basis for using the name, since Edward III of England was known as “Edward

of Windsor” in his early years.

On July 27, 1917, King George V issued a proclamation in which he renamed his royal house and family Windsor and renounced the German titles that he and his family held. The proclamation

was

significant as it allowed male-line descendants of Queen Victoria without the

dignity and style of HRH Prince or Princess

to use Windsor as their surname. This was necessary for two reasons. Firstly,

George also issued Letters Patent that limited the dignity and style of a

British prince and princess to children of a monarch, male-line grandchildren

of a monarch, and the eldest living son of the eldest son of the Prince of Wales.

Secondly, George V and Queen Mary had decided to allow their children to marry

native British men and women, because hitherto, it was largely unheard of for

royalty to in effect, marry their subjects, which explained the tendency to

marry members of other royal families (particularly Protestant ones based in

Germany). These two reasons guaranteed that there would be descendants of

reigning monarchs without princely titles who would require a surname.

|

| Arthur Bigge, Baron Stamfordham, the man who suggested Windsor as a family name for George V and his family in 1917. |

|

|

Windsor Castle.

Built by William the Conqueror, it has been a royal residence since Henry I of

England, and extensively modified and enlarged by successive English and

British monarchs.

|

On July 27, 1917, King George V issued a proclamation in which he renamed his royal house and family Windsor and renounced the German titles that he and his family held. The proclamation

|

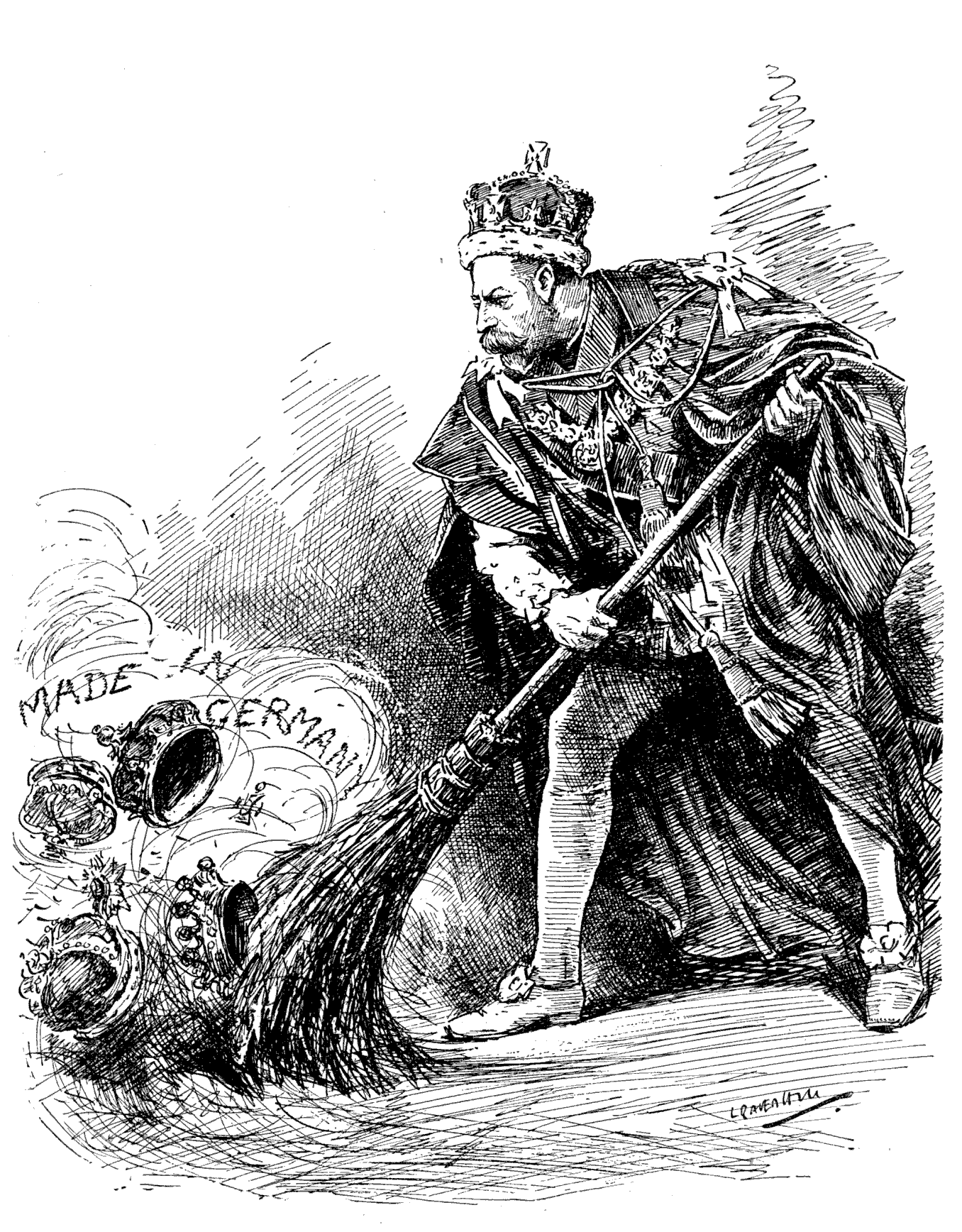

| Good Riddance: King George V sweeping away his titles "Made in Germany" |

In practice however, the name has been used by

titled members of the royal family for birth registrations, marriage

certificates, and other purposes. For example, the reigning queen’s father –

the future George VI, who was then styled as His Royal Highness Prince Albert, Duke of York –

was listed as “Windsor, Albert F.A.G. (Duke of York)” in an official index of registered British marriages in 1923. The initials F.A.G. stand for his middle

names, Frederick Arthur George, and the maiden name of his bride, Lady Elizabeth

Bowes-Lyon, is listed in the column next to him.

|

| The marriage of Albert F.A.G. Windsor (the future George VI) to Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon as listed on an official marriage index. Source: Freebmd.org.uk |

|

| The birth of Elizabeth A.M. Windsor (the future Elizabeth II), as listed on an official birth registration index. Source: Freebmd.org.uk |

|

| The names of Philip Mountbatten and Elizabeth Alexandra Mary Windsor as written on the marriage register of Westminster Abbey. |

|

| The birth of Charles P.A.G. Windsor (Prince Charles) as listed on an official birth registration index. Source: Freebmd.org.uk |

But upon Elizabeth II’s accession in 1952, the question of the name of the

royal family was re-opened. She had married Philip Mountbatten, Duke of

Edinburgh (formerly Prince Philip of Greece and Denmark), and like most women,

it was thought that she would take her husband’s name and that Mountbatten – the name of Philip’s

maternal relatives in Britain which he adopted upon his naturalization as a

British citizen – would be the name of their descendants. After her accession, Philip’s uncle, Lord Louis Mountbatten (known as

“Dickie”), boasted at a dinner party that the “House of Mountbatten” now

reigned. This insolent comment got around to Elizabeth’s grandmother, Queen Mary who convinced

Prime Minister Winston Churchill that Windsor

– the name chosen by her husband George V back in 1917 – and not Mountbatten ought to be

the name of the royal family. Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother (Elizabeth II's mother) agreed with

Churchill and Queen Mary, and the new reigning queen herself wished to stick to the name

of her father and grandfather. On April 9, 1952, she issued a statement

reaffirming that her house and family would continue to bear the name Windsor.

|

| Queen Mary was not amused about the prospect of the royal family becoming the House of Mountbatten. |

In reality however, the House of Windsor would have continued throughout the

Queen’s reign. Traditionally, female monarchs reigned as members of the house/surname

into which they had been born, while their successors reigned as members of the

house/surname of their husband. For example, Queen Victoria was born into the

House of Hanover, and reigned as the last monarch of that house in the United

Kingdom. Her son, Edward VII became the first monarch of the House of

Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, the ancestral house of his father and Victoria’s

husband, Prince Albert. So by convention, the “House of Mountbatten” would not have come about until the accession of Prince Charles (or his male-line heirs).

But in 1952, there were members of the British

establishment who had

been suspicious of Philip from before his marriage to Elizabeth. He had been a penniless Greek prince who came from a Germanic background – having been born into the German-Danish House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Glücksburg – and his sisters had

all married German princes, some of whom had Nazi connections. Philip did have an honorable record serving in the Royal Navy during World War

II, but his foreign background and brash temperament made him an outsider to the British establishment (which hoped that he would simply do no harm to the monarchy). His “Uncle Dickie”

connections with

the royal family to create a more “progressive” monarchy that would shape government policy. So the establishment simply

did not want the Mountbatten name to be plastered on the monarchy in the generations

yet to come, and wanted the Queen, in writing, to state that Windsor would be

the name of her house and the name that her descendants would carry. (Mountbatten would eventually have his own last laugh against Churchill and the establishment by becoming First Sea Lord some forty years after his father's forced resignation.) For his

part, Philip was not enthusiastic about the Mountbatten surname, but

nonetheless believed in the general principle that his children and future

descendants ought to take his name, and he explained the traditional passing of

royal house names to Churchill and members of his cabinet (see previous

paragraph). Though Philip was historically correct, the Cabinet rebuffed this,

as well as his attempt to find a compromise with names such as Edinburgh and

Edinburgh-Windsor (based on his title, Duke

of Edinburgh). He bitterly complained to a friend that he was nothing but

“a bloody amoeba,” unable to pass his name on to his children like other men.

|

|

The Duke of

Edinburgh wanted to have a name

representing his side of the family, but the young Queen sided with her establishment adviser's and stuck to the Windsor name. |

The issue remained a sore point for Philip in the

early years of the Elizabeth’s reign. But by 1960, with the death of Queen Mary

in 1953, the resignation of Churchill in 1955, and the withdrawal of much of

the old guard at the Palace and in government, the Queen decided to make an

attempt to lay the issue to rest. On February 8, 1960, after extensive talks

with her ministers and advisors, the Queen announced a compromise in which her

royal house and family would continue to be known as Windsor, but that her and Philip’s male-line descendants without

the style and dignity of HRH Prince or Princess

would bear the surname Mountbatten-Windsor.

(It should be noted that this change did not affect the Queen’s male cousins

through George V and Queen Mary – the Duke of Gloucester, Duke of Kent, and

Prince Michael of Kent – or their descendants, whose surname remained Windsor). But the effect has

been that

the surname has been available for use by all of the Queen’s children and

her descendants with British princely titles on occasions when a surname may be necessary (such

as on birth and marriage certificates). Princess Anne signed her name as Mountbatten-Windsor upon her 1973

marriage to Captain Mark Phillips, and her maiden name is listed as such on the

1977 birth registration index containing their son, Peter Phillips. The children

of Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex – who do not use the royal titles afforded to

them by birth – are styled as children of an earl: Lady Louise Mountbatten-Windsor

and James Mountbatten-Windsor, Viscount Severn. (Prince Edward’s secondary

title is Viscount Severn, and it is customary for the eldest son of a man with

aristocratic titles to use the secondary title, known as a courtesy title).

|

| Mountbatten-Windsor is listed as Princess Anne's maiden name on the birth registration list containing her son, Peter Phillips. Source: Freebmd.org.uk |

But there is one more wrinkle in all of this:

members of the royal family who have territorial titles (i.e., Prince of Wales)

can use the territorial designation of such titles as an informal surname. For example, Prince Edward was known as “Edward Windsor” during his time working in

the entertainment industry, but upon becoming Earl of Wessex in 1999, he became

professionally known as “Edward Wessex.” Prince William – whose formal title

before

becoming Duke of Cambridge was

Prince William of Wales – decided to

be known as “William Wales” while he attended the University of St. Andrews as

well as during his military career, and Prince Harry has done the same (owning to the fact that their father is the Prince of Wales). The

recently-born Prince George of Cambridge will probably be informally known as “George

Cambridge” for similar purposes. This is why members of the royal family are

sometimes referred to as the Wales's (Prince of Wales & family), Cambridge’s (Prince William, Duke of

Cambridge & family), York’s

(Prince Andrew, Duke of York & family), Wessex’s (Prince Edward, Earl of Wessex & family), as well as the Kent’s and

Gloucester’s (who are the Queen's cousins through George V and Queen Mary), and so on.

In the final analysis (and to give a straight answer), Mountbatten-Windsor is the surname of the royal family of Queen Elizabeth II, but the members of the family with the style and dignity of HRH Prince or Princess are not required to use it except perhaps for circumstances in which a surname may be necessary, such as signing birth and marriage certificates. Such members can use informal surnames derived from the territorial designation of their titles or just the titles themselves without any surname at all, which explains the absence of a surname on Prince George’s birth certificate.

It should be noted that the name of the royal house and family can change at any time, either at the behest of a reigning monarch, or by the accession of a monarch with a different house and family name than the previous one. Upon Prince Charles becoming king however, it is not expected that he will make changes to the name of the royal family, and that the he and his family will continue to be of the House of Windsor, whilst the formal surname will continue to be Mountbatten-Windsor.

|

| Flight Lieutenant William Wales |

In the final analysis (and to give a straight answer), Mountbatten-Windsor is the surname of the royal family of Queen Elizabeth II, but the members of the family with the style and dignity of HRH Prince or Princess are not required to use it except perhaps for circumstances in which a surname may be necessary, such as signing birth and marriage certificates. Such members can use informal surnames derived from the territorial designation of their titles or just the titles themselves without any surname at all, which explains the absence of a surname on Prince George’s birth certificate.

|

|

On his birth

certificate, Prince George was written in as

His Royal Highness Prince George Alexander Louis of Cambridge. |

It should be noted that the name of the royal house and family can change at any time, either at the behest of a reigning monarch, or by the accession of a monarch with a different house and family name than the previous one. Upon Prince Charles becoming king however, it is not expected that he will make changes to the name of the royal family, and that the he and his family will continue to be of the House of Windsor, whilst the formal surname will continue to be Mountbatten-Windsor.

| The Badge of the House of Windsor |

Photo Credit: Mark S. Jobling via Wikimedia Commons cc, German Federal Archives (Bundesarchiv) via Wikimedia Commons cc, BiblioArchives/Library Archives via Flickr cc, Robert Payne via Flickr cc, Sodacan via Wikimedia Commons cc

Sources:

Marr, Andrew. The Real Elizabeth: An Intimate Portrait of Queen Elizabeth II. New York: St. Martin's Press. 2012. Print (Pages 22-25, 50-53, 74-77, 88, 135-137).

Smith, Sally Bedell. Elizabeth the Queen: The Life of a Modern Monarch. New York: Random House. 2012. Print (Pages 146-147).

No comments:

Post a Comment